Recently, I had the distinct pleasure of interviewing Amy Meissner in the context of my Luscious Legacy Project. The conversation was so rich and we covered so much ground … from legacy to art to writing to nourishment … I just knew I had to share her genius with a much wider audience. This post has been edited from the longer voice interview. Enjoy!

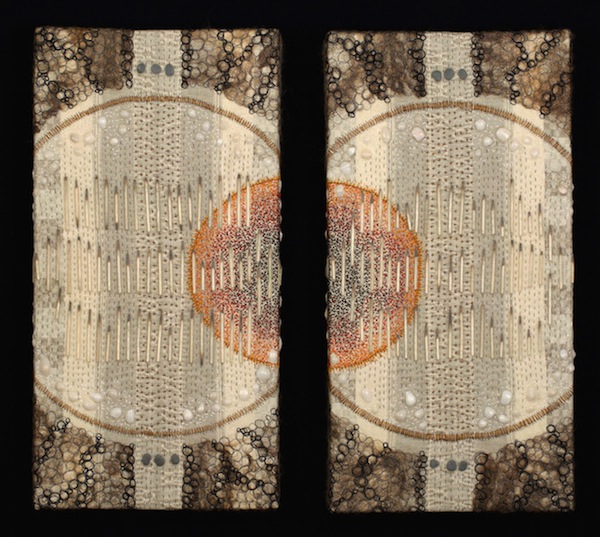

Amy Meissner is a mother, a maker, and a textile artist whose art combines traditional handwork and contemporary imagery to explore themes of the body, fear and loss. Her materials are vintage, discarded or found.

Amy has shown in museums and galleries in Alaska and in the Lower 48, with award-winning work residing in the permanent collection at the Anchorage Museum and in several private collections. She is a recipient of a Rasmuson Foundation Fellowship Award and lives and works in Anchorage, Alaska.

Her current passion, The Inheritance Project, is a beautiful representation of what it means to honor articles and artifacts of generations past. When I stumbled upon her work, I was captivated by the dance between past and present … the stories and artifacts of our past and how they weave themselves together, sometimes purposefully, often mysteriously, into the narrative we’re living and breathing today. A luscious legacy, indeed.

Sue Ann: Welcome, Amy. I am so excited to be interviewing you in the context of my Luscious Legacy Project. I’d like to begin with your roots. Will you tell us about your lineage?

Amy: My mother was raised by her grandparents on a farm in Sweden, but came to the United States in 1965 when she was nineteen. She had a great uncle in California who’d left Sweden a number of years before and offered her an opportunity to live with him and go to school. He paid for community college, bought her a sewing machine (which she still has), bought her a car. He had a lovely housekeeper who doted on her and insisted on taking my mom shopping.

She has amazing, bright memories of this time. She was away from the farm and her grandmother’s iron fist for the first time, finding an independence in America. That Swedish farm was of such a different time and place. She doesn’t remember anyone ever sitting down to read a book, there was just too much work to do. I can’t speak for the country of Sweden, but I can speak to my mother’s memories of this farm and the people who raised her. Swedes are stoic. They are serious, hard-working people. Obviously we can crack through that and find a sense of humor, but on the surface, at least in that family, there’s perhaps a misperception about warmth. The reality is, I think they are incredibly focused and have a strong work ethic. I see this in myself, I even see that misperception about warmth. Sometimes I’m far too serious.

Sue Ann: Tell us about your current love affair, textile art. I loved what you shared about your children, your struggles in the realm of Mama, and how those struggles actually enrich and inform your art. Will you tell us about that?

Amy: I approach making this kind of art work in the same way I would approach a piece of memoir, the writing form I’m drawn to most: I circle. Mary Karr talks about this in The Art of Memoir. She describes it as circling around your fears to find an entryway. That resonates with me because sometimes you don’t know where a piece is going. Maybe there’s a moment or an unclear memory that you want to focus on, and you don’t really know why you feel compelled to explore it. You don’t want to write to theme, but you want theme to emerge from the writing – I feel the same with visual art. There are a lot of things I consider throughout a project, but what it keep coming back to is fear. A lot of it is fear- or loss-based for me, so I circle around that question.

There’s a balancing act with motherhood that I’m checking in with all the time. I find it difficult to take care of myself, but I know I can’t take care of my family properly if I don’t. I make sure that I have those quiet moments and listen for that voice whispering in my ear or flashing an image before my eyes, then quick write it down because it’s not going to come again. The muse has disappeared enough times that I really try hard to remain attentive.

Sue Ann: I know the mamas and teachers in my community would be so interested to hear the story behind The Acquisition of Language piece.

Amy: I made this piece at a time in my family’s life when we’d experienced some severe ailments: broken ankles with subsequent surgeries, a sinus surgery, ongoing back issues. The stack of medical papers was incredible and I felt like my husband and I had started communicating through this pain-based language. And then my children started doing it, too. Part of it was their age – a dropping into themselves and becoming more aware of their physical bodies – but it seemed like every day something hurt, for someone.

I wanted to explore how we acquire language, especially the language of pain. I use a lot of found objects in my textile work, embedding bone, shell, stone and wood. I also incorporated a lot of text in this piece, creating a free motion cursive script with the sewing machine, following a list of every single thing in our household that anybody ever said “hurt.” Moving the fabric beneath the machine for hours was very physical, this litany of my knee, my ankle, my toe, my head, my tongue, my tooth… it just went on and on and on and on, and I had to take breaks from the sewing. My whole body hurt from it. I also had flashbacks from Mrs. Landry’s third-grade class where I first learned how to write in cursive. That was some crazy muscle memory.

Another portion of the piece embroidered onto an old table runner says, “Why do you always say that something hurts?” And this could be me asking my husband that question, or me asking my children, or them asking me, or me asking my parents, “Why does something always hurt? Why can’t it just be?” A final hand embroidered list runs through the center of the piece. In our prior conversation you referred to it as poetry, which shocked me because I didn’t come to the work thinking, “I’m going to write a poem, edit it a billion times, and shrink and shrink it and shrink it until it’s absolutely the most potent use of language possible and the most minimal essence of each word.” I didn’t have that sort of intent. I came to it with the idea of litany – this on and on and on kind of feeling that accompanies chronic pain.

I’ve watched people in galleries stand and read from the piece, then come stumbling away because it has this deep emotional feel to it. When I work by hand, it’s so slow I have time to think about what the next bit of language is going to be or where the next move will land; it’s as if I’ve already gone through all the editing already by the time I stitch the next word. If I’d written the same poem on paper, I probably would have spent exactly the same amount of time on it, though the poem would have been completely different written off of the cloth. I don’t know if it would have had the same heft.

Sue Ann: I am deeply curious about what we keep and what we pass on. When I happened upon The Inheritance Project, I was captivated. Here you are collecting these pieces of handwork as a vehicle to explore voice and history and narrative. For me, it feels like such an honoring. Where did it begin? When did these Mystery Boxes start coming?

Amy: Family members in Sweden have always sent me linens and handwork, but I’ve rarely used any of these things for my home. They’ve been stored in my trunk for years until I started using the cloth in my artwork. Then I received an email last summer from a woman I’d never met in upstate New York who really wanted to send me a collection of vintage linens. I have to admit the alarm bells went off but I wrote back with my address and said, “No anthrax, no fire bombs.”

When the box came, my daughter and I opened it on the deck, and inside were all these vintage pointy bras and seamed stockings, linens and doilies. She and I had the best time going through it. Her brother had a friend over that afternoon and she was feeling a little left out, and it was also a time when our relationship felt strained. She was starting first grade and had a lot of fear that manifested in snotty remarks towards me and lashing out at her brother; just this really unsettled presence about her. But that afternoon felt really pure. We tried on bras and held up stockings, and then we caught the boys spying on us through the sliding glass door and we laughed and screamed. It’s just this lovely visceral memory I hope she’ll always have.

I don’t know the woman who sent this to us or who had owned the items before, but we made up a lot of stories and we guessed and wondered. I felt strongly that the experience was informing the next phase of my work. It felt important.

After I blogged about it in a post called “Box of Mystery,” other people contacted me and things started arriving and I realized right away I had to keep track of everything. These were objects that deserved and needed documenting, spreadsheets, proper thank you cards and shaping.

I also realized I’d need to put parameters around the project if I didn’t want people emptying out their cupboards and sending all their unwanted things to me, so there’s a formal list of items I’m looking for. I’m also asking for information: who the maker is, what the origin is and what the circa is because I feel like this also needs honoring. For the most part, all three of those things aren’t readily known, and that in itself feels so powerful to me. I keep envisioning this list of makers of which 95% will be labeled “Unknown.”

This process of collecting, documenting and corresponding with people is vital to what I now call “The Inheritance Project.” I’m inheriting things originally inherited by others. And there’s an understanding that very few of these items are going to remain intact once I begin working with them. People are okay with this. If they’ve spent time looking at my artwork at all, they understand I’ll make something else out of the linens they send. Up until this point my work has been really personal, like memoir, using moments, experiences or fears and transforming them into a piece of artwork that then people bring their experiences to and have responses based upon their own history.

Now, I’m feeling a shift and want to explore the fictional aspect of these items. I’m curious about the mythology generated by this vast pool of artifacts that have little or no history. I feel a connection to these unknown makers, and the narrative gurgling up is something I’d like to explore through the next series of work I make from these items. I’m still shaping it and unsure what the end result will be, but I’m envisioning an exhibition with a written component and a combination of two-and three-dimensional work.

Sue Ann: I think what I’m hearing you say is that there’s power in allowing the shaping to occur as it will. That there’s this inherent trust that you have that these pieces are going to come together in a multi-faceted way, but I really sense from you that it’s going to happen in its own time.

Amy: I think a big part of creating is being patient, and that’s really hard because the world is so fast-paced. Artists, creators, makers need quiet, allowing the luxury of no media, no sound, even if it’s for five minutes. We get so little quiet time to just let the answers come. And they will come, so you have to be ready. They aren’t going to be the answers you thought you were looking for either, but you still have to listen to the muse. She will land on your shoulder and whisper in your ear, and then you have to act or she might not come again.

Sue Ann: Are you seeing any patterns emerging with regard to people who are sending you these pieces? Who are they? What are they saying?

Amy: There’s a sense of value, and it’s clear people hang onto these items for various reasons even if they don’t know the provenance. Others find them out in the world and rescue them. There is value in the handmade, value in the valueless and useless. So few of us have doilies under every single thing like my grandmother did — I remember seeing a tiny doily on her bathroom windowsill with some little thing on it and thinking, “There are doilies everywhere!” Consciously collecting them is such an irony. I can’t believe I’m doing it.

There is also pain in letting go. A woman shared recently that she sat with her mother-in-law while she chose what to take with her to an assisted living home. This woman’s role — so emotional to me even now — was to bear witness to these objects and the stories that they held, helping her mother-in-law transition into the next phase of her life. I think this is a common pattern as well, the downsizing, whether or not by choice.

Sue Ann: I’m so curious about something you said in one of your posts: Your words: “I also love language and stories and voice, and believe old things have a lot to say, especially about the women makers who couldn’t or wouldn’t say what they needed to say, instead burying their pain or anger or fear with each stab of needle or hook.” I know in my nourishment work with women that making art can be vehicle for healing old wounds. I believe you’re saying something very different here. Will you elaborate?

Amy: I think about this a lot with regards to women’s work. On the farm where my mother grew up, no one took time to sit and read a book or look at a magazine or nourish themselves in that creatively visual way. But what they did take time for was domestic making and mending. Women were allowed to do this work because it was productive. So, I often wonder about those moments of quiet at the end of the day when a woman could steal that time for herself and bury everything she couldn’t say throughout the day — all the comments she kept to herself, all the thoughts and ideas that maybe went against what the men in the household had to say or think. This was her time to dump it all into the act of making and transform it into something beautiful. The monitored brain lights up when people who are knitting, for example — the whole screen lights up! While I am saying something a little different, I think it’s still the same.

Louise Bourgeois said something about sewing as an act of emotional healing or mending. It’s true. You bury those things or transform them into something else you can bear to look at.

Sue Ann: So, what are you learning about yourself in this process?

Amy: I’m learning about looking ahead. While I’ve tried my whole life to plan everything the best I could, I need to be open and let my art and the Inheritance Project take shape the way it’s going to because these are truly “Boxes of Mystery” arriving that I have no control over. If something is really unusable, or a rag, I’m not going to save it. I already told myself that I don’t have to. But, it’s interesting that the things I initially find so completely ugly or base are often the things I reach for first. So, what I think I’m trying to do is not only be open, but also remain naïve because this is a vital part of creating anything whether it’s a piece of writing or a piece of artwork. If one can maintain an innocence and a naiveté going into a project, I think you can still be open to that purity, that unlocking of the door, that circling to find the heart of a piece. You don’t necessarily go into it knowing what the heart is, but hopefully you come away from the work having found it.

![]()

I hope you enjoyed reading this interview as much as I enjoyed conducting it! Be sure to check out the links below so that you can see more of Amy’s genius.

website | Facebook | Instagram

If you are interested in learning more about The Inheritance Project please click on the image below!

The photographs of Amy’s art were taken by Brian Adams, amazing photographer and Native Alaskan. You can learn more about him right here.

10 thoughts on “Amy Meissner is Leaving a Luscious Legacy”

Wow. What a creative piece in itself. I was thinking of what Amy said about how women were ‘allowed’ to do these creative things because they were productive. It got me thinking how we have lost the purpose or meaning behind our ‘crafts’ … sometimes. it’s not for survival anymore … at least not in the same way as it was … it is a different survival now. A survival of mending and healing, not only of the craft but of the heart and the soul and the meaning of being a woman who mends and heals with her hands for her family, for herself … for the world…

Love how it’s making me feel deeply into the lineage of being a woman … in a different kind of way…

Thanks for reading and responding so fully, Elizabeth. I’m still pondering so many of the gems in this conversation. For me, the making, allowing myself the ‘process’ without purpose is an ongoing journey. Feeling a deep resonance with your mention of a different survival now … more like a spiritual survival … for ourselves and for the planet. xxoo

Wow Sue Ann!! I feel like you have met your kindred spirit. What a beautiful conversation and a magical meeting of passionate and creative souls. As I was reading this I could imagine a documentary; you in Amy’s studio asking questions and being mesmerised by her stories and Amy in your kitchen doing the exactly the same. Inspiring the world to honour our luscious heritage. Goosebumps.

Synchronicity to hear you say this, Angela, because steeping myself in these words, first through the lens of legacy, and then later through the lens of a ‘maker’ left me wanting the conversation to continue. This line especially gave me pause: “While I’ve tried my whole life to plan everything the best I could, I need to be open and let my art and the Inheritance Project take shape the way it’s going to because these are truly “Boxes of Mystery” arriving that I have no control over.” That’s pretty much how my entrepreneurial life is unfolding. Thanks for reading and responding lovely one. xxoo

I’ve been enjoying Amy’s work and words through Facebook. This article about her thoughts, plus the photos, is so inspiring. Our Guild’s next show theme is “Quilting Economics”, so the idea of rescue work can be incorporated into that. I want to share this with all of them! And it helps justify my sentimental “hoarding”! 🙂 Thanks to Amy, Sue Ann, and Brian.

Sentimental hoarding, ha, ha, yes, I can so relate. (Especially my books!) One of my Luscious Legacy members recently shared with me that when she had to downsize, she took photographs of some her beloved sentimental objects and artifacts so that she could keep them in digital form. I got to thinking that could be yet another facet of this LLP project: What We Keep. Thank you for taking the time to respond to this post, Kathryn. xxoo

there is so much here to grasp and unravel and ponder and absorb. the way amy honors the inner processes that women go through, and recognizes how they transform so beautifully into outward expression is truly inspiring. (and those pictures of her daughter! priceless.)

The kind of interview you want to sit with and ponder, yes. Thank you for reading and responding, April. xxoo

“I honor the makers” says Amy on her blog. I’m so grateful to you, Sue Ann, for introducing me to this lovely woman who makes beauty out of the language of our pain. Collecting bones. Tying fragments of our lives into our tapestries so we can see the whole textile and make sense of it.

“We get so little quiet to let the answers come,” oh yes! But they do come when we invite the quiet. When we are are tenacious about the quiet. And they are OUR answers. Like the glorious day Amy shared with her daughter. A day made for healing and personal mystery and future map making that guides a life and family.

When I was growing up, my step mother, who is a visual artist, took her mother’s and grandmother’s doilies and glued them to boards. Then she took rubbings of them. Then drew and painted back into them. I was treated to story after story of women’s artwork. The culture of women and how women brought art west. Quilters and makers.

She was one of the original “Front Rangers” who made a statement about western women and the future of women’s art. She is a maker. And it matters.

Thank you for this lovely view of legacy. And history. And art.

“She is a maker. And it matters.” Yes. Thank you so much for sharing all this, Rebecca. Every time I read this interview I feel graced by the presence of ‘honoring’ at so many levels.